To answer this question, we need to step back and ask, “Why do we need land reform in the first place to solve the global poverty problem?” Land reform can improve agricultural productivity and rural livelihoods. Since the majority of the global poor population lives in rural areas and depends on the agricultural sector for their livelihood, land reform can potentially help alleviate global poverty. According to a recent World Bank report, agricultural development is one of the most powerful tools to end extreme poverty and boost shared prosperity. Implementing land reform can lead to growth in the agricultural sector, which has been demonstrated to be two to four times more effective in increasing the income of the poorest compared to other sectors.

In my research, I found two main reasons why land reform can succeed in some countries but not others. First, land reform thrives in countries with smaller agricultural burdens. Agricultural burdens comprise factors that impede labor movement out of the agriculture sector and factors that hinder agricultural productivity. Second, land reform fails in countries where conflicting political and agrarian relations between the state and peasants predominantly shaped the political development of agriculture, which I conceptualized as disembedded peasantry.

Agricultural burdens and land reforms

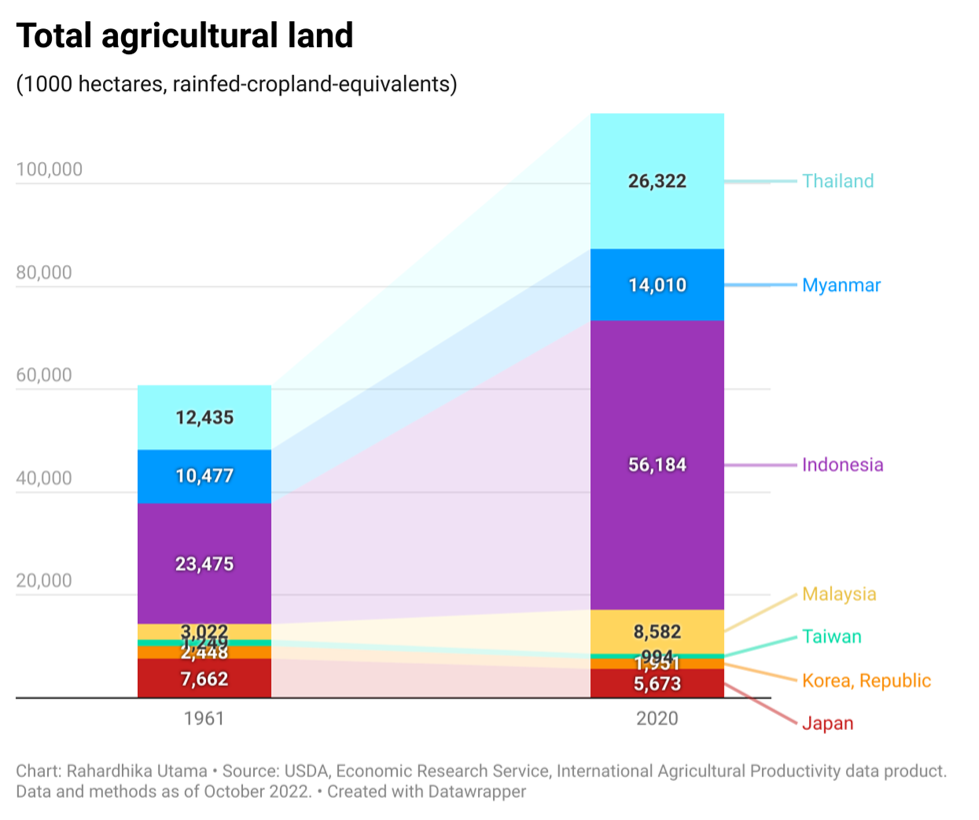

Historically, countries with a large agricultural sector encounter more significant agricultural burdens than those with a smaller agricultural sector. A larger agricultural economy requires extra effort and resources to mobilize labor out of the agricultural sector into more productive sectors, upgrade agricultural technology, and implement other agricultural reform initiatives such as land reform. Asian transformational economies such as Japan, South Korea, and Taiwan have been historically endowed with less agricultural land and agricultural labor compared to Indonesia, Thailand, and Myanmar. Hence, the latter group of economies encounters more agricultural burdens than their transformational counterparts. With sizeable agricultural land and a large agricultural workforce, these economies have more barriers to improving land productivity and moving labor into more productive sectors.

The endowment of large agricultural areas posits challenges for a country to achieve high-level productivity. The larger the land area, the more difficult and costly it would be to invest in infrastructure for technology adoption and structured policies that promote agricultural productivity, including land reform. For example, Indonesia and Myanmar have a significantly larger endowment of agricultural land area compared to South Korea, Japan, and Taiwan, and the differences in the total agricultural area between these groups of countries have become more significant over time. Indonesia’s agricultural land area exceeded South Korea’s by a factor of nine in 1961. By 2020, however, the difference in agricultural land area between the two countries had grown significantly, with Indonesia’s agricultural land area being 28 times larger than that of South Korea. Therefore, land reform has been more successful in economies with smaller agricultural burdens, such as Japan, South Korea, Taiwan, and Malaysia, than in Indonesia, Myanmar, and Thailand, which carry more substantial burdens.

In the context of the Asian rubber belt, agricultural burdens were legacies of the colonial plantation economy, an economic system based on large-scale agricultural production, typically cash crops, prevalent in many colonies during the European colonial period. While Malaysia managed to address its agricultural burdens to achieve a higher level of economic development through implementing transformative agricultural reform since the 1960s, Indonesia has failed to do so. I maintain that the state’s ability to address agricultural burdens is contingent upon the political development of agriculture, which is predominantly shaped by political and agrarian relations between the state and peasants.

Peasantry embeddedness and land reform

Peasantry embeddedness is a type of political approach to agricultural development stemming from patterns of agrarian and power relations between the state and peasants. In the Asian rubber belt, the colonial plantation economy has left a legacy of the state’s control over land ownership. Hence, the agrarian and power relations that drove the political approaches to agricultural development are the power dynamics between the state as an entity with authority to control land ownership and peasants, wherein the state can control, influence, and manipulate the behavior of peasants in matters related to the agricultural economy. These power relations are reflected in the form of rent, coercive measures, subsidies, and distributed resources orchestrated by the state that impact the livelihood of peasant communities.

I identified two types of peasantry embeddedness in the Asian rubber belt. In Indonesia, the agrarian conflicts resulted in the institutionalization of the disembedded peasantry, wherein the state neglects—and to some extent represses—peasants in agricultural development. In this type of peasantry embeddedness, the state disregards peasant interests and the overall agricultural sector. In contrast, the configuration of the embedded peasantry in Malaysia allows for a congruent relationship between the state and peasants. Further, it promotes thriving agricultural development, including the implementation of transformative land reform policies. The variation in peasantry embeddedness between the two countries is rooted in the critical events of peasant emancipation and peasant repression in the first twenty years after the end of colonialism in the region.

Indonesia

The state-organized violence against peasants from 1965 to 1967 in Indonesia led to the configuration and perpetuation of the disembedded peasantry. The peasant massacre set in motion a series of events that culminated in the state’s rejection of peasant-centered agricultural development after 1967, including the cancellation of national land reform programs and the rise of elite military control over large agricultural assets.

Before the 1965 to 1967 massacre, the Basic Agrarian Law (BAL) enacted in 1960 signified Indonesia’s commitment to supporting peasant emancipation. The law was the result of advocacy by the communist party and peasant political leaders. It replaced the colonial land tenure system and sought to limit control over large plantation lands by foreign planters. The law also institutionalized land reform efforts to support the smallholder economy. It appeared that Indonesia would continue to pursue a development agenda centered on peasant emancipation, supported by leftist and nationalist leaders within the government and parliament.

The massacre changed everything. It brought to power an anti-communist military regime that dismantled the land reform agenda due to its association with leftist politics. The army seized plantations and land assets across the archipelago, labeling peasants and plantation workers as communist sympathizers to justify land dispossession. In the following decades, military and state elites controlled much of the agricultural sector, focusing on state-owned plantation industries rather than smallholder empowerment. As a result, land reform never recovered as a national priority.

Malaysia

In contrast, colonial Malaya began to adopt peasant emancipation measures in the 1950s to boost rubber output during the Korean War. These measures, introduced alongside counterinsurgency campaigns against communist guerrillas, sought to stabilize rural areas by improving conditions for smallholders. This early experience with peasant emancipation laid the groundwork for a more cooperative relationship between the state and rural communities.

After independence, that legacy endured. Peasant participation in political movements through the United Malays National Organization (UMNO) strengthened their voice in shaping agricultural policy. The government established several major agricultural development agencies, including the Federal Land Development Authority (1965), the Federal Land Consolidation and Rehabilitation Authority (1966), the Malaysian Agricultural Research and Development Institute (1969), and the Rubber Industry Smallholders Development Authority (1973). These institutions supported land redistribution, technology adoption, and smallholder development. Malaysia’s embedded peasantry thus helped ensure that land reform became a sustained and successful national project.

Conclusion

Agricultural burdens can inhibit the success of land reform policies. Countries with larger agricultural land areas and workforces face more barriers to reform and modernization. Moreover, the relationship between the state and the peasantry determines whether reform can take root. When that relationship is antagonistic, as in Indonesia, land reform tends to fail. When it is cooperative, as in Malaysia, reform can thrive.

Agricultural burdens and peasantry embeddedness together offer a useful lens for understanding why some agrarian economies of the global south have managed to reduce poverty while others remain trapped in inequality.

Note:

This post was originally published in the Problem Solving Sociology blog as part of the series “What Can Sociology Bring to Solving Global Poverty?”. It draws from my dissertation, “Embedded Peasantry and Economic Transformation in the Asian Rubber Belt,” which examines Indonesia, Malaysia, Thailand, and Myanmar, countries historically shaped by the colonial rubber plantation economy.