I used to believe that inequality weakens democracy. The more unequal a society becomes, the more disconnected people feel from the political system. Why would someone vote if the decisions are always made by the wealthy few?

But as I started looking at data from Indonesia, that belief started to shift. What I found was more complex, and in some places, more hopeful than I expected.

Inequality does not always silence people. Sometimes, it wakes them up.

This is a story about data, but also about people. It is about what happens when ordinary citizens face deep economic gaps, and what that means for political voice and power.

When the Data Does Not Match the Assumptions

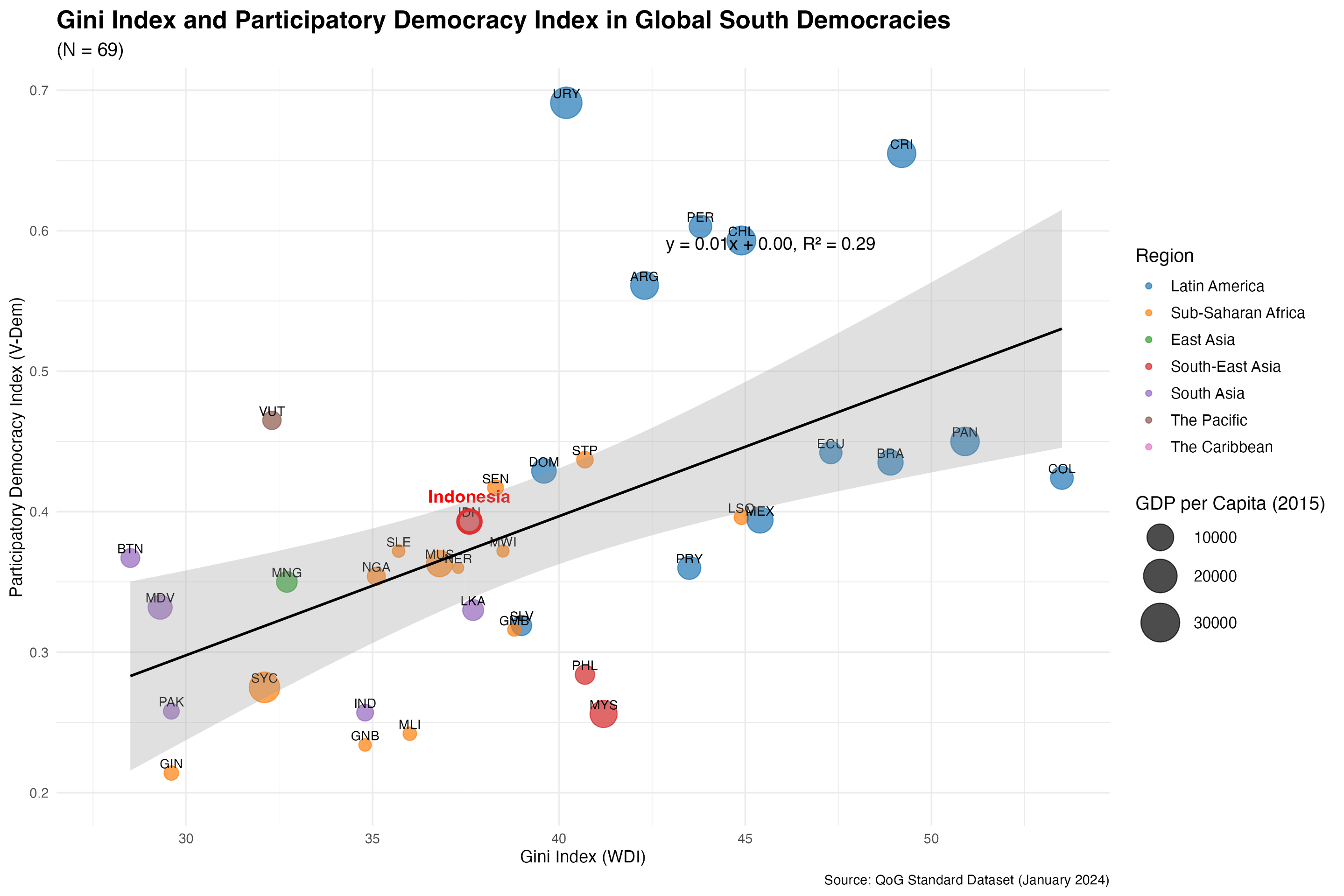

I began with a global comparison. On one axis, income inequality using the Gini coefficient. On the other, levels of participatory democracy. I expected to see a clear downward slope. More inequality, less democracy.

I began with a global comparison. On one axis, income inequality using the Gini coefficient. On the other, levels of participatory democracy. I expected to see a clear downward slope. More inequality, less democracy.

Instead, I saw something else. A weak but noticeable positive correlation. In many countries, higher inequality was associated with more political participation.

Indonesia’s position on that chart stood out. We have moderate inequality, but our level of participatory democracy is lower than expected. That gap became the starting point for a deeper exploration.

To understand what was happening, I turned to two influential ideas from political theory. Each one tells a different story about how inequality and democracy relate.

Two Theories, Two Stories

The first is called Relative Power Theory. This theory argues that inequality makes political participation more difficult for those with fewer resources. When wealth is concentrated in the hands of a few, those few gain outsized influence over the political system. The poor, in contrast, may lack the time, money, or belief that participating will make a difference (Goodin and Dryzek 1980; Solt 2010).

According to this view, people disengage because they feel excluded. The system favors the rich. The political class listens to the elite. Over time, this imbalance leads to voter apathy, especially among the marginalized (Bartels 2008; Hacker and Pierson 2010).

The second is known as Conflict Theory. It tells a different story. When inequality becomes too extreme, it can trigger political action. People become aware of injustice and demand change. Political participation increases, not because the system is working well, but because people are angry enough to try to change it (Gurr 1970; Cappelen et al. 2013).

This theory suggests that both the rich and poor may become more active during periods of high inequality. The rich seek to protect their interests. The poor mobilize for redistribution and reform (Mahler 2002; Brady 2004).

Both theories are compelling. And in Indonesia, both seem to apply. But only when you look closely.

What the Provinces Tell Us

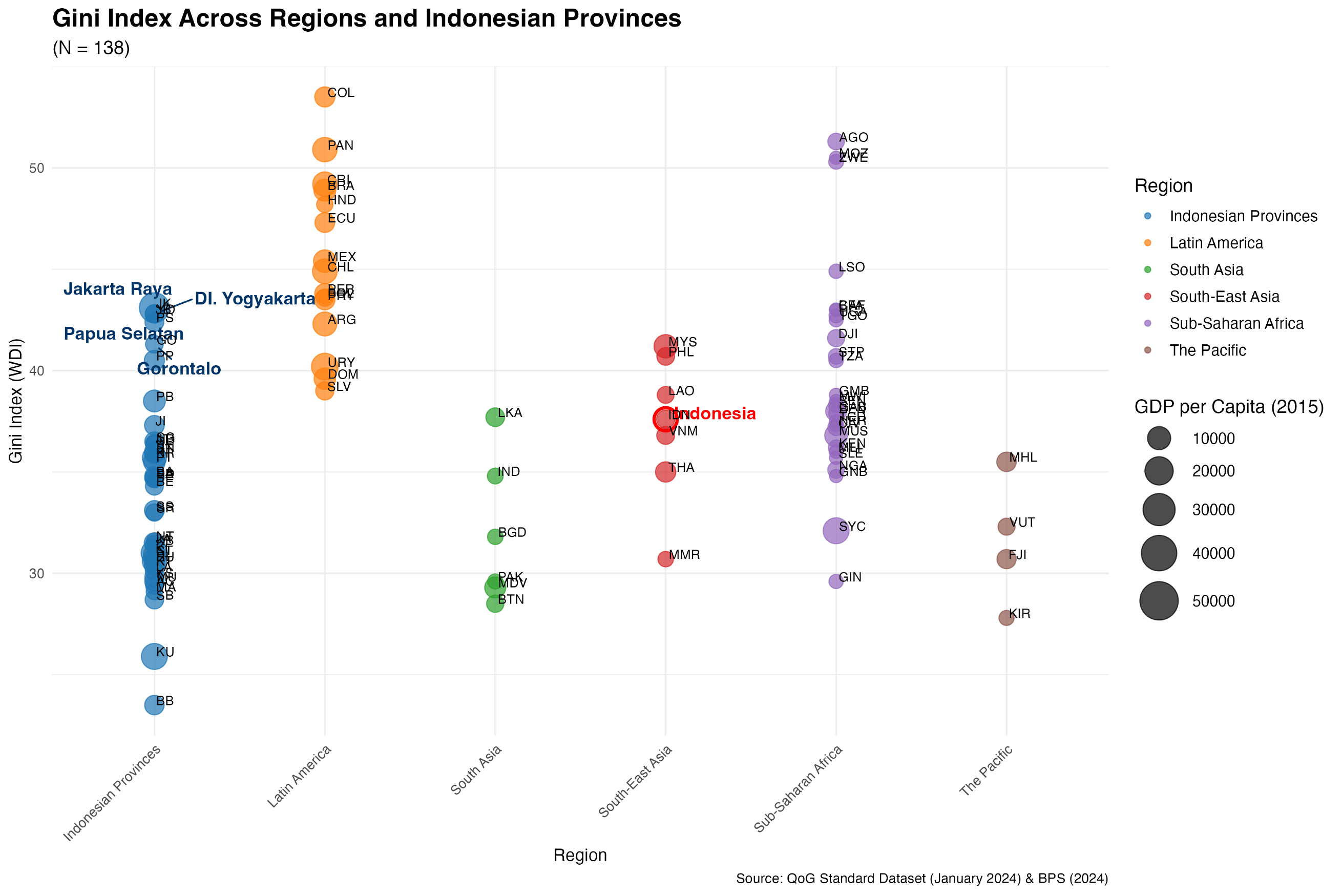

I began by looking outward. Before digging into Indonesia’s provincial data, I wanted to understand where we stand globally.

The comparison was sobering.

Some provinces in Indonesia have levels of income inequality that are nearly on par with the most unequal regions in the world. DKI Jakarta and DI Yogyakarta, in particular, stood out. Their Gini coefficients are comparable to countries like Bolivia and Peru, and even higher than Malaysia and the Philippines.

Some provinces in Indonesia have levels of income inequality that are nearly on par with the most unequal regions in the world. DKI Jakarta and DI Yogyakarta, in particular, stood out. Their Gini coefficients are comparable to countries like Bolivia and Peru, and even higher than Malaysia and the Philippines.

This is not just a statistical quirk. It is a reflection of the deep structural divides that exist within our own borders. These are not just gaps between individuals. They are gaps between entire provinces, between urban centers and rural districts, between those with access to opportunity and those without.

In many ways, Indonesia contains multiple economic realities within one nation. That means inequality is not just a national issue. It is a subnational challenge. And addressing it requires attention not just from Jakarta, but from every corner of the country.

With that in mind, I turned to the question of how inequality might shape political participation at the local level.

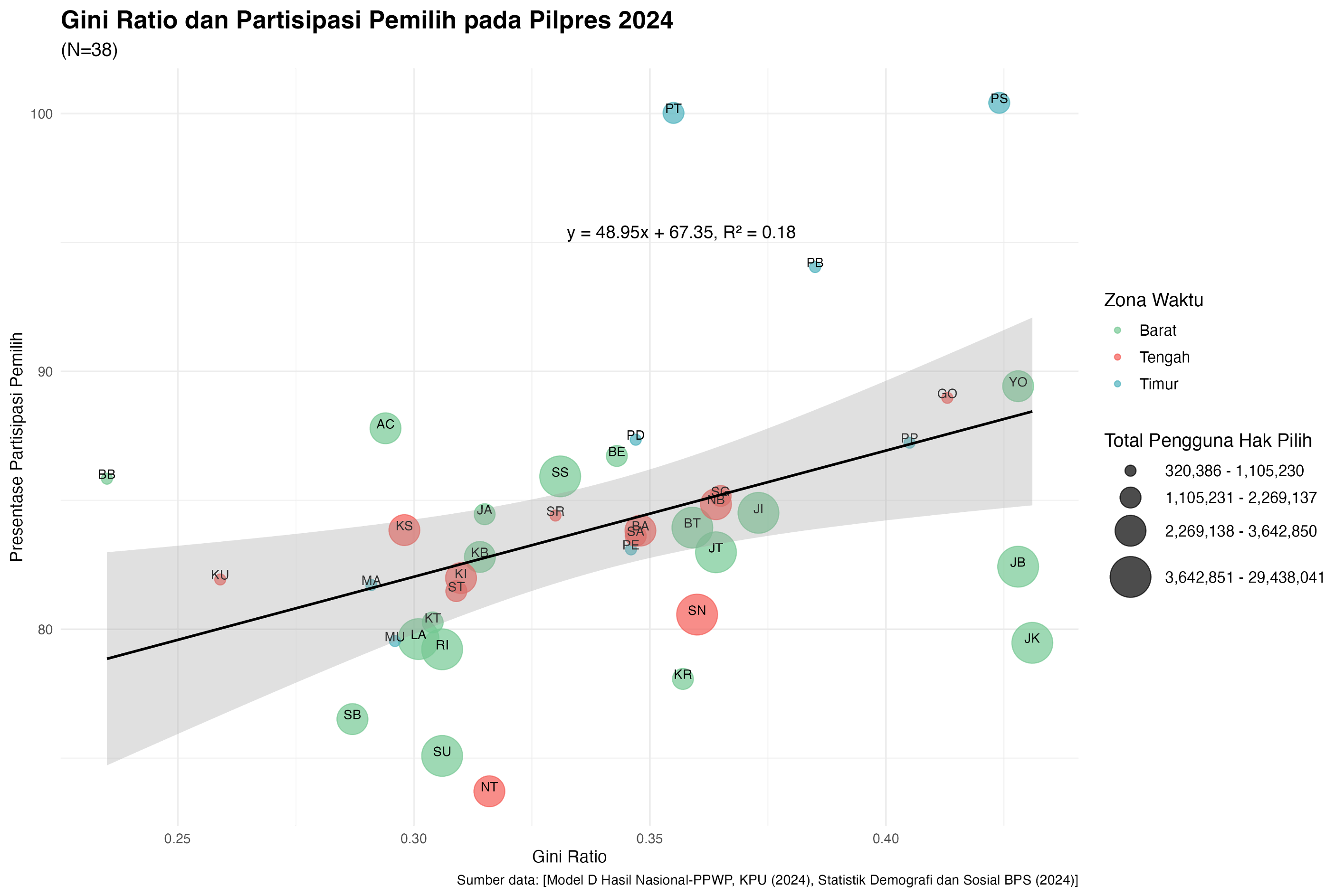

Using data from the Central Statistics Agency (BPS) and the General Election Commission (KPU), I examined voter turnout across Indonesian provinces and compared it to income inequality in each region.

One pattern stood out. Provinces with higher income inequality tended to show higher voter turnout. Yogyakarta and Gorontalo were two clear examples. Both regions have some of the highest inequality in the country, and yet both report strong participation in elections.

This finding aligns with the logic of Conflict Theory. In these regions, inequality may not be causing withdrawal from politics. Instead, it might be fueling engagement. People are voting not because they feel included, but because they feel excluded. The ballot becomes a response to frustration, a demand for change.

But the picture is far from uniform. In some areas, inequality seems to inspire action. In others, it leads to silence. That variation tells us that inequality does not operate in isolation. It interacts with local culture, economic history, gender norms, and access to political space. And those interactions shape who shows up, and who feels left out.

Gender Shifts the Pattern

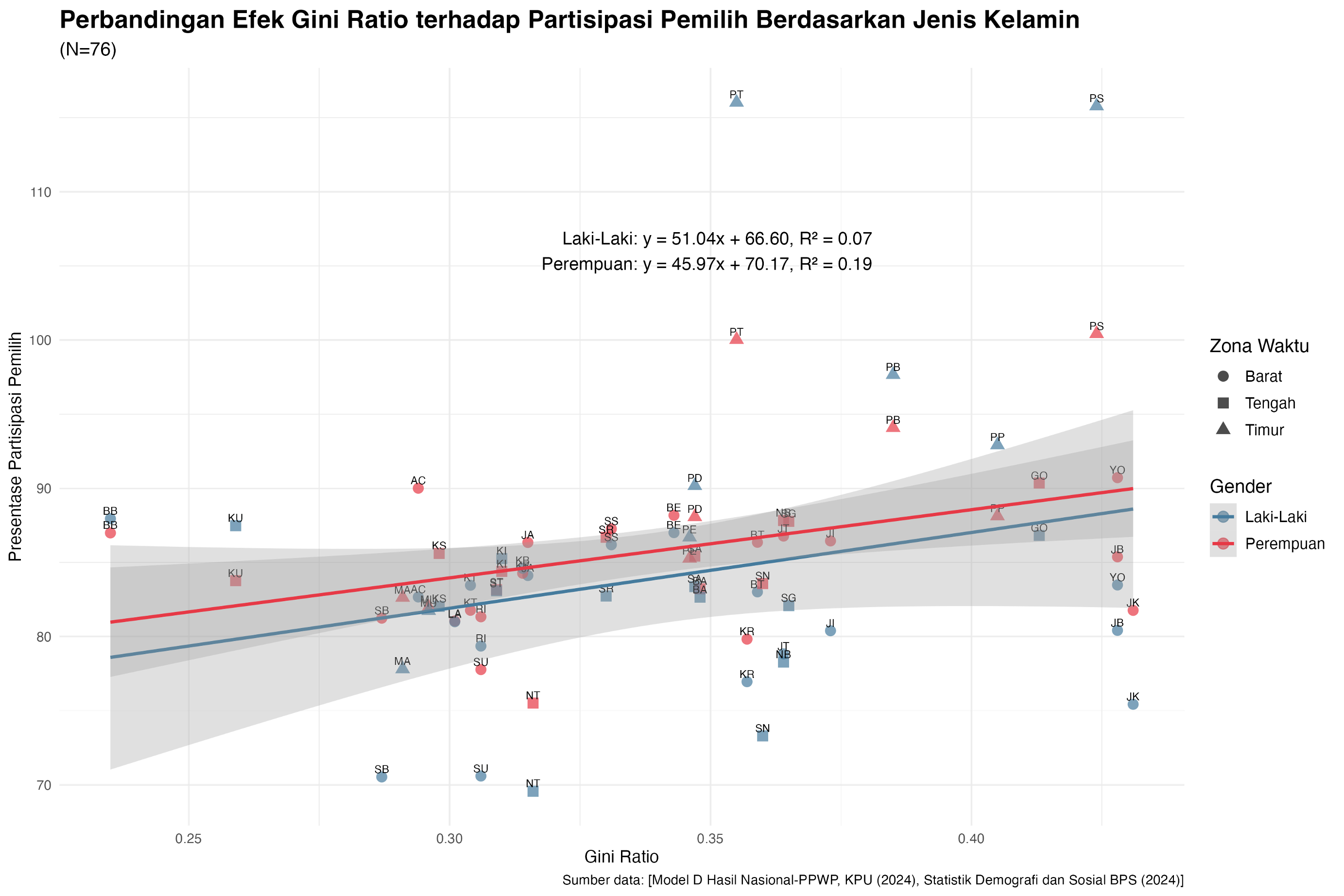

When I separated voter turnout by gender, a new pattern appeared. In many regions, as inequality increases, women become more likely to vote than men.

This could be because women often experience inequality in more layered and personal ways. Economic stress often translates into greater burdens in care work, household budgeting, and food security. Voting may become one of the few tools available to demand better outcomes.

However, this pattern changes in the eastern provinces. There, inequality is more strongly associated with increased participation among men. Women’s participation remains flat or shows a weaker connection.

These differences suggest that inequality interacts with local norms and gender roles in complex ways. In some places, it mobilizes women. In others, it motivates men. No single theory explains everything. The local context matters.

Poverty and the Question of Place

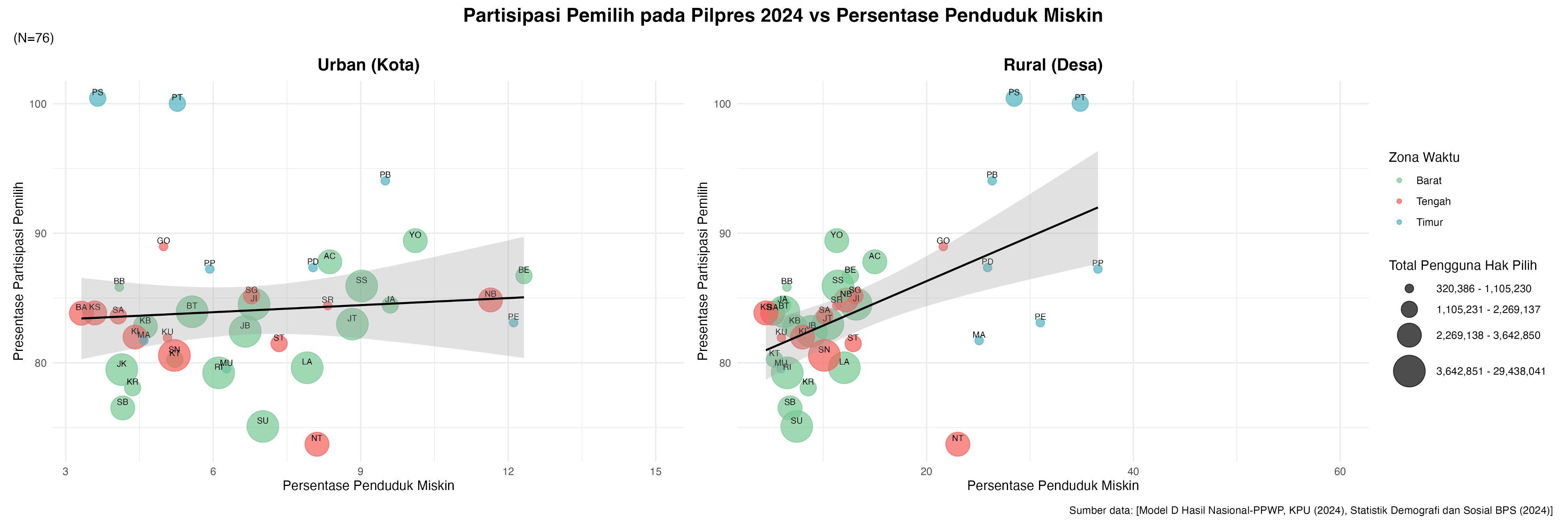

I also looked at poverty, measured by the percentage of people living below the poverty line. The effect of poverty on participation depends on where people live.

In urban areas, poverty does not seem to influence voter turnout. The data shows almost no change. Poor urban voters may feel that their votes do not matter or may face practical barriers to participation.

In rural areas, the story is different. Poverty there is linked to higher voter turnout. The poorer the community, the more likely people are to vote.

This pattern suggests that rural voters may be more connected to their communities. There may be stronger local organizing, closer relationships with candidates, or more visible stakes. In these places, political engagement becomes a path to survival and dignity.

Eastern Indonesia Speaks Louder

The eastern provinces are worth special mention. These areas tend to have both high inequality and high poverty. Despite that, they often report some of the highest voter turnout in the country.

That outcome challenges the idea that exclusion leads to silence. In these communities, exclusion seems to fuel engagement. People do not retreat. They act.

Why This Matters

The relationship between inequality and democracy is not simple. Sometimes inequality suppresses participation. Sometimes it provokes it. The outcome depends on geography, gender, and social conditions.

This means national averages can be misleading. Voter participation in Jakarta will not look the same as in West Papua. Women and men may respond differently to the same conditions. Urban poverty creates different effects than rural poverty.

If we want to strengthen Indonesian democracy, we need to stop relying on uniform solutions. We need strategies that are responsive to real conditions on the ground.

The Role of Social Movements

Data can tell us a lot. But behind the numbers are people. And people do not just react. They organize.

Where inequality exists without collective action, change is unlikely. But when communities come together, inequality can become a reason to act rather than a reason to give up.

This is where social movements matter. They give voice to the excluded. They build networks of trust. They translate frustration into political pressure. They create space in a democracy that often tries to shrink.

Final Reflection

Democracy is not just about voting. It is about being heard. In a country as large and diverse as Indonesia, that means listening to how inequality actually works in people’s lives.

Some may disengage. Others may mobilize. The key is understanding who is being left out and why. That is where the real work begins.

This blog is based on early-stage research conducted in collaboration with IFAR Atma Jaya. The findings were originally presented at a public discussion hosted by Oxfam Indonesia and Yayasan Penabulu, titled “Memusatkan Perhatian pada Ketimpangan untuk Mencapai SDGs”, held on January 23, 2024.