What happens when young people come face to face with stories of civic repression? Does knowing more about activist persecution make them more critical of elites, more likely to act, or more inclined to retreat? These questions lie at the heart of an experimental study we conducted with Indonesian youth, designed to explore the relationship between awareness, political trust, and civic engagement.

Through a simple but carefully structured experiment, we examined how a brief informational message about activist repression shaped young people’s attitudes. The results speak to broader dynamics unfolding across Indonesia—how trust varies by region, how past experience shapes future action, and why raising awareness alone may not be enough.

A Brief Experiment, A Bigger Question

Participants were randomly assigned to one of two groups. The control group answered survey questions without any added context. The treatment group received a short prompt describing recent instances of activist repression in Indonesia—cases drawn from credible public reporting. Afterward, all participants answered questions about their trust in political elites, their willingness to engage in activism, and their readiness to commit time, money, or energy to civic causes.

The survey was fielded online between November 2024 and March 2025. Out of 809 responses, we focused our analysis on 457 youth who met the age criteria. This design allowed us to isolate the effect of the repression prompt while controlling for region, prior activism experience, and other background factors.

Trust in Elites Depends on Where You’re From

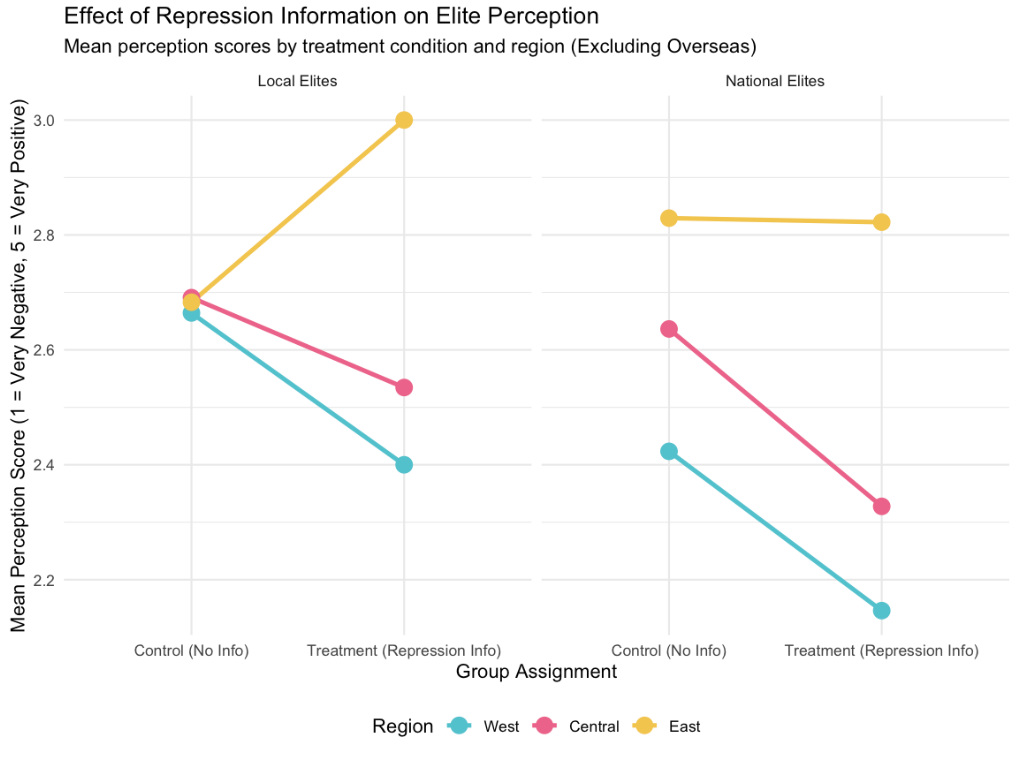

In the first stage of the experiment, we examined how the informational prompt shaped perceptions of national and local elites.

In Western Indonesia, the treatment had a clear effect. Young people who were exposed to the repression message rated both national and local politicians more negatively than those in the control group:

For national elites, the difference was statistically significant (2.15 vs. 2.41, p = 0.034), as it was for local elites (2.40 vs. 2.67, p = 0.024). Post hoc analysis confirmed that this region had the most pronounced response to the treatment, likely reflecting longer-standing grievances and higher political awareness.

In Central Indonesia, the shift was more muted. There was a marginal decline in trust toward national elites (2.33 vs. 2.64, p = 0.067) and an insignificant change for local elites (p = 0.368).

In Eastern Indonesia, exposure to repression information had no effect on national elite perceptions (2.82 vs. 2.82), and trust in local elites actually increased slightly in the treatment group (3.00 vs. 2.68, p = 0.084):

These regional contrasts suggest that political attitudes are not shaped by information alone. Historical context, prior exposure to repression, and state-society dynamics vary widely across Indonesia—and so does the political meaning of that information.

Awareness Isn’t Enough to Spark Action

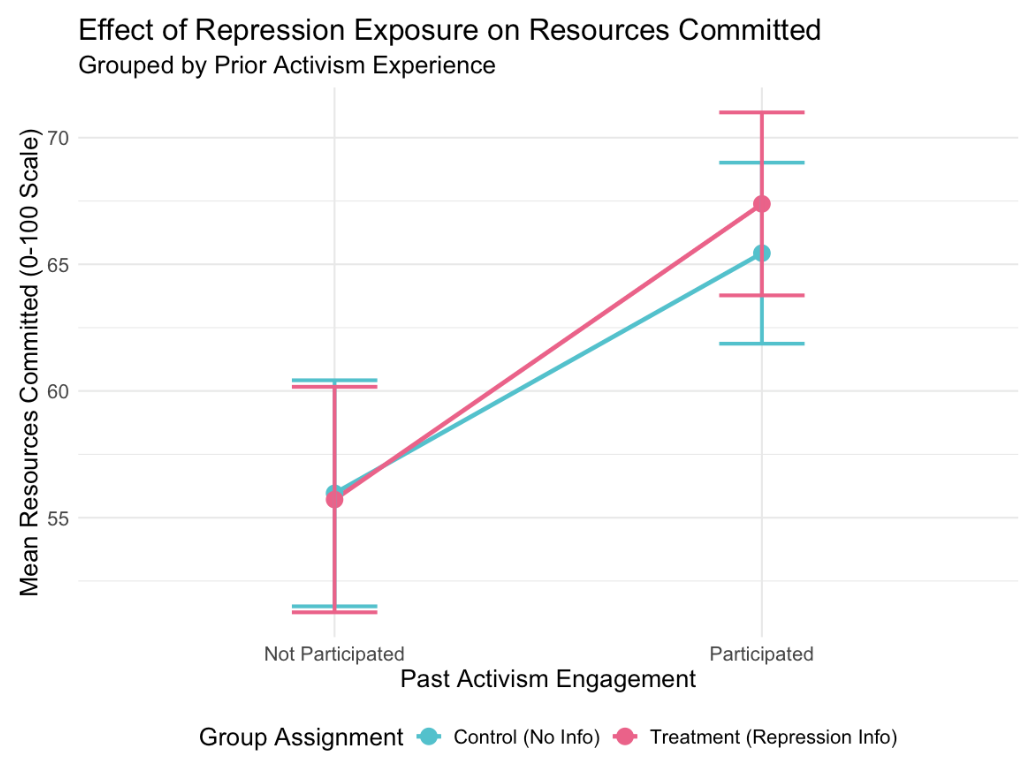

The second part of the experiment tested whether exposure to repression made participants more likely to commit resources to activism.

The treatment effect was not statistically significant (p = 0.229). Simply reading about civic repression did not make respondents more inclined to invest time, money, or effort in activism:

But one factor did: prior activism experience. Individuals who had participated in activism before were significantly more likely to commit resources, regardless of whether they saw the repression message (estimate = 0.599, p < 0.001).

Post hoc comparisons confirmed this across both groups. In the control group, prior activists scored 0.575 higher in willingness to commit (p < 0.001); in the treatment group, the gap widened to 0.681 (p < 0.001).

This points to a self-reinforcing dynamic. Engagement builds on itself. Youth who have already taken part in civic activities are far more likely to stay engaged, while informational prompts alone do little to move those without prior experience.

Willingness to Join Civic Organizations

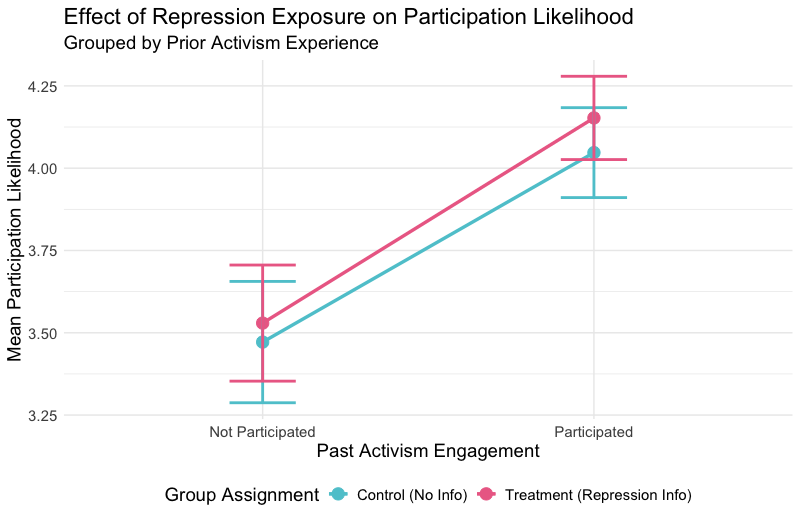

In the third stage of the experiment, we looked at another measure of engagement: the likelihood of joining civil society organizations (SMOs).

Once again, prior activism was the strongest predictor (F(1,462) = 57.80, p < 0.001). Exposure to repression had no statistically significant impact (F(1,462) = 1.45, p = 0.229), nor did it interact meaningfully with activism history.

Among those without prior experience, the treatment made no difference. Among those who had participated before, it also made no difference:

This reinforces the broader lesson: exposure to repression alone is not a reliable motivator for political engagement. What matters most is whether someone has already found a way in.

Implications for Youth Engagement

This study adds to a growing body of evidence on the limits of informational interventions in authoritarian or semi-authoritarian settings. In the Indonesian context, simply exposing youth to civic repression is not enough to galvanize new forms of engagement. Regional context matters. Political memory matters. But most of all, experience matters.

If we want to strengthen civic space and democratic participation, especially among youth, the path forward lies not just in raising awareness, but in building durable entry points. Youth engagement is not sparked by outrage alone. It is sustained through opportunities to act, spaces to learn, and communities to belong to.

This finding has broader implications for Southeast Asia, where democratic backsliding is reshaping the terrain of civic life. As spaces for activism narrow, movements must not only adapt tactically. They must also invest in onboarding the next generation.

This post draws from a larger research agenda on social movements, civic space, and democratic backsliding, with a focus on youth activism and the future of democracy in Indonesia. As democratic erosion reshapes how politics works on the ground, our research explores how young people and civil society actors navigate and respond to shrinking civic space. Through national surveys and extensive fieldwork, Muhammad Fajar and I examine how social movements adapt under pressure and what this reveals about democratic resilience in Southeast Asia.

This project is part of an ongoing collaboration with Yayasan Partisipasi Muda.

Read the full report: Fajar, Muhammad and Utama, Rahardhika. Understanding Youth Engagement and Civic Space in Indonesia. Jakarta: Yayasan Partisipasi Muda, 2025. download the full report here.

Listen to our interview at The Conversation: We spoke about how shrinking civic space is affecting young Indonesians’ ability to express themselves – now available on The Conversation.